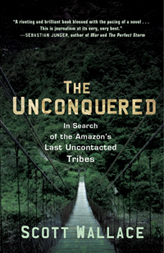

Scott Wallace's bestselling book about tracking an uncontacted tribe in the deep Amazon is available in all formats.

More information

WATCH THE UNCONQUERED TRAILER HERE

About Scott:

Scott Wallace is a writer, producer and photojournalist who seeks out original, compelling, character-driven stories. His assignments have taken him from the deepest Amazon to the Alaskan Arctic, from clandestine arms bazaars in post-Soviet Russia to snatch-and-grab missions in the slums of Baghdad.

https://www.high-endrolex.com/8

Read his full bio here.

Watch Scott's exciting bio clip here

lovekesu