Costa Rican Murder Shines Light on Poaching, Drug Nexus

June 18th, 2013

by Scott Wallace

The murder of an environmental activist in Costa Rica has shaken the country’s ecology-minded public and has cast a light on what appears to be the growing overlap between animal poaching and drug trafficking on the country’s Caribbean coast.

Early on the morning of May 31, masked gunmen abducted 26-year-old Jairo Mora Sandoval from a vehicle he was using to patrol a desolate beach to protect nesting leatherback turtles from poachers.

Four international volunteers who were accompanying Mora were bound and taken to a nearby shack, from which they eventually escaped. Mora’s body was found later the same day, facedown in the sand and exhibiting signs of torture.

Almost three weeks later, police continue to search for Mora’s killers.

The murder has triggered shock and revulsion throughout Costa Rica. At recent candlelight vigils for Mora across the country, protesters called on government officials to bring those responsible to justice and to make good on promises to strengthen protections for Costa Rica’s natural treasures and the people who defend them.

“The government has failed in its responsibilities,” said social psychologist Carolina Rizo, as she stood in the rain amid hundreds of other demonstrators at a vigil last week in San José, Costa Rica’s capital.

“It’s been left to young volunteers to do what the state should do,” she said. “To be as ecological as our image suggests would require a commitment to laws and standards. People don’t do the jobs they’re supposed to do.”

With a history of political stability, a relatively low crime rate, and dozens of protected areas teeming with biodiversity, Costa Rica markets itself as an idyllic travel destination for eco-adventures and outdoor family fun.

But many officials share Rizo’s concerns that weak and ineffective enforcement of Costa Rica’s environmental laws belies the country’s image as an eco-friendly tropical paradise, especially on the sparsely populated, impoverished Atlantic Coast.

“It’s an area where there is an extremely low presence of authority,” said Juan Sánchez Ramírez, an investigator with the nation’s Environment Ministry. “The government has neglected the region. People must find a way to live by whatever means they can.”

For many people on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast, Sánchez and other officials say, that means trafficking in protein-rich eggs ransacked from turtle nests. Turtle eggs flavored with hot sauce are served in popular restaurants and sold by street vendors along the Caribbean coast.

At the same time, the poachers have been drawn into the tightening grip of drug runners coming north up the coast from Panama and Colombia in souped-up speedboats designed to outrun authorities.

“The geographical position of the country makes it an ideal place for the transit and warehousing of drugs,” said Erick Calderón, commander of Costa Rica’s uniformed police, the Civil Guard, in the palm-fringed coastal city of Puerto Limón.

“But it’s not all in transit,” he said. “Some of it stays here and, worse yet, traffickers are using drugs to pay local distributors. That means it has to be consumed here, which creates and sustains a local market.”

According to officials and residents of the Limón area, cash-strapped users are turning to turtle eggs to finance their addiction, even trading the eggs directly to drug dealers for powdered cocaine. A single nest can yield up to 90 fertile eggs, and egg poachers, known as hueveros, frequently dig up several nests in a single night’s work. The eggs are sold on the black market for $1 each.

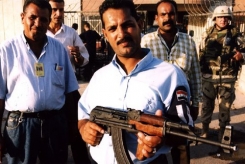

Poachers now brandish high-powered weapons that were rarely seen before on Costa Rica’s shores, most notably AK-47s. “The police don’t even have AK-47s,” said Sánchez, the environmental investigator, “but the traffickers have them.”

His claim is borne out by colleagues who worked with Jairo Mora and have reported confrontations with heavily armed poachers while patrolling Moín Beach, a hauntingly beautiful and desolate stretch of coastline just north of Puerto Limón.

The very conditions that have made the area’s beaches a favorite nesting spot for magnificent leatherbacks and other turtles—their remoteness and the lack of artificial light or human infrastructure—make them a haven of choice for smugglers and poachers.

And that makes them ever more dangerous for the environmentalists who are trying to save the critically endangered turtles.

“Sometimes the [drug] boats come directly onto the beach,” said one resident. “That’s why they don’t want anyone out there patrolling. They don’t want people to see what’s going on.”

There’s no comprehensive way to prevent turtle nests from being pillaged, advocates say, without a permanent police presence on every stretch of beach during the four-month nesting season.

“The poachers are always watching us from the trees,” said Vanessa Lizano, head of Moín’s Costa Rican Wildlife Sanctuary, who was a close friend of Mora’s. “So if we hide the nests or move the eggs to another place on the beach, they find them anyway.”

For Lizano and her colleagues, the preferred method is to gather eggs shortly after they’ve been laid—or even while the mother turtle is laying them—then bury them in a hatchery that’s guarded by volunteers.

But one night last year, masked assailants raided the hatchery at gunpoint, confiscating cell phones and walkie-talkies while making off with the entire trove of 1,500 eggs.

Activists have reduced their own nightly patrols along Moín since Mora’s death, even as police have stepped up their presence. Like NGO personnel and volunteers, the police typically employ foot patrols out on the sand, shadowed by a vehicle that must maneuver through dense palm groves along a narrow dirt track paralleling the beach.

It’s an assignment fraught with risk, said police commander Calderón, and also with frustration.

“The poachers can see our headlights from far off,” he said. “They hide their eggs and run into the forest. They pick up where they left off as soon as we’re gone.”

While much of Costa Rica’s Atlantic Coast is protected as part of the national park system, Moín Beach is not.

Supporters of Jairo Mora Sandoval are petitioning the government to make the 15-mile-long beach a national park to honor the memory of the valiant young man who gave his life to protect the turtles he loved so much.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.