Photo Gallery

CAUGHT BETWEEN IRAQ AND A HARD PLACE

© 2003 by Scott Wallace

Our Fighting Forces Struggle to Bring Stability to Baghdad

By Scott Wallace

Published in the Mid-York Weekly Review and Pennysaver, October 16, 2003

Published in the Mid-York Weekly Review and Pennysaver, October 16, 2003

I arrived in Baghdad one evening in early July as the setting sun drew a crimson band across the western horizon on the far side of the Tigris. I’d followed the main road up from Kuwait in an air-conditioned SUV with an armed driver, crossing vast stretches of shimmering desert where bandits are known to lurk. This was the same route U.S. forces had followed last spring in the rush to Baghdad. My burly driver, a former security guard in Saddam’s army, kept a loaded pistol in the console between us.

“What if we get stopped by Ali Baba?” I asked when we departed Basra that morning, bound for Baghdad. I hadn’t yet realized how common a phrase the mythical name – Ali Baba – has become in the mayhem of post-Saddam Iraq. It’s come to mean – to Americans and Iraqis alike – any sort of criminal element, and in today’s Iraq, they abound: highwaymen, carjackers, kidnappers, pickpockets, looters. “I don’t stop for nothing,” he replied in broken English.

We reached the relative safety of Baghdad seven hours later without incident. Fortunately, the pistol remained cold and unused in the console when I bid farewell to the driver and handed over $250 in cash for the lift.

Within a few days of my arrival, I joined an Army patrol through central Baghdad to get a first look at the challenges facing American forces trying to bring order to the chaos. I hiked with a squad of GIs for several blocks, all the while followed by a small herd of Iraqi kids, who tugged at our sleeves. “Hey, meester, how are you?” they shouted playfully. “Hey meester, what you name?” We turned off the street and entered the surreal gloom of Saddam’s Ministry of Information building. As my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I could see the place had been thoroughly trashed.

It had been bombed at the outset of the war, but the structure of the building was intact. The real destruction came at the hands of looters in the wake of Saddam’s fall. We picked our way through the darkness, ducking twisted shards of metal that hung from the ceiling and stumbling over incredible wreckage: charred fuse boxes, busted filing cabinets and plate glass windows smashed on the floor.

As we passed the pitch-black stairwell, we heard a babble of Arabic voices echoing through the barren chamber. Cpl. Blake Gibson wheeled around with his M-4 rifle pointed into the stairwell and turned on the flashlight mounted to his gun. Three men – faces and hands blackened with soot – were coming down the stairs dragging burlap bags.

“Get down!” Gibson barked. The men needed no translator. They dropped facedown on to the cement floor. Their sacks were stuffed with copper wiring. “Are there other Ali Babas upstairs?” Gibson and the other soldiers asked. “How many Ali Babas – two, three, four?”

The looters were “zip-stripped” – bound with plastic zip cuffs – before we dashed up the stairs in search of their companions. Several flights up, we came upon another pair of young vandals as they laid into a phone box on the wall with a hacksaw.

In all, the soldiers rounded up eight looters and marched them back for processing at a sandbagged checkpoint at the entrance to Saddam’s old palace compound. Too bad, I thought, the troops didn’t engage in this kind of crackdown from the very beginning. But now, Iraq’s entire infrastructure lay in shambles, a whole new criminal culture had emerged in the power vacuum left by the collapse of the Saddam regime, and a guerrilla resistance had begun to congeal. And this was a part of Baghdad that was relatively free of crime and violence.

In all, the soldiers rounded up eight looters and marched them back for processing at a sandbagged checkpoint at the entrance to Saddam’s old palace compound. Too bad, I thought, the troops didn’t engage in this kind of crackdown from the very beginning. But now, Iraq’s entire infrastructure lay in shambles, a whole new criminal culture had emerged in the power vacuum left by the collapse of the Saddam regime, and a guerrilla resistance had begun to congeal. And this was a part of Baghdad that was relatively free of crime and violence.

“We’ve got this part of Baghdad under control,” said a tall soldier with sergeant stripes on his shoulder as he approached me. “We went after the curfew violators right away. We zip-stripped anyone who looked cross-eyed at us.” He spoke with authority and confident optimism. A brief conversation ensued. I finally got around to asking the sergeant where he was from. “Upstate New York,” he said. Really, I asked, whereabouts? “Utica,” he replied.

His name was Alec Lazore, 38, and he grew up on Seymour Avenue in the 1970s and graduated from Proctor High School in 1982, before he joined the Army. His father, Ralph, still lives on Howard Ave., he told me. Lazore is the 1st Sergeant, the second in command, of Alpha Company, 2nd Battalion, 6th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Armored Division.

From that day on, Lazore and his troops took me out on several operations and patrols. I went with them at midnight on a “snatch and grab” mission in search of a Fedayeen commander. I accompanied them on a sweep of an apartment complex to look for weapons. Meanwhile, I got acquainted with former NYPD commissioner Bernard Kerik, who had taken up duties as Top Cop in post-Saddam Baghdad. I went out with Kerik’s team in search of kidnappers who were using ransom money to finance resistance operations.

What impressed me most of the month I spent in Baghdad was the fragility of the peace that U.S. forces sought to impose, and how vulnerable they remained to attack from the moment they ventured beyond the sandbagged checkpoints that guard the entrances to Saddam’s palace compound that now serves as headquarters for the Coalition’s occupation government in Iraq.

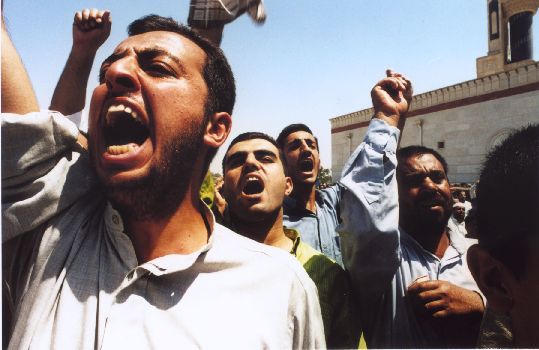

I attended worship services one Friday noon at a mosque on the western edge of Baghdad, an area known as a hotbed of anti-American resistance. After the worship, the imam delivered a blistering diatribe inciting Iraqis to wage jihad to expel the foreign occupiers. I didn’t see another American face among the thousands attending the services. Certainly, it would have been even more dangerous than it was for me for a U.S. official to be present in that angry mob.

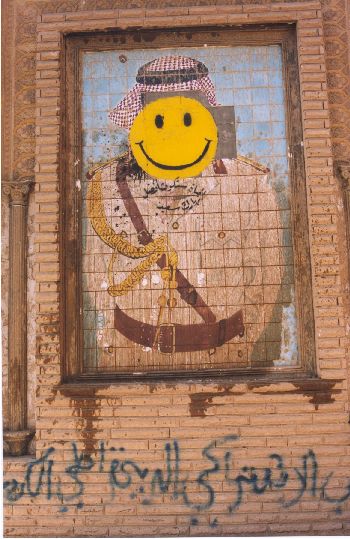

And yet, without taking such risks, Americans can neither know what’s really going on in Iraq, nor can they counter the vitriol of the anti-American propagandists. I noted a rather deep well of goodwill among the Iraqi people toward our presence in their country. But arbitrary arrests, and our failure to bring order, have sapped much of Iraqi’s patience. And the longer we stay, the easier it becomes to blame us for everything that is going wrong, even the multitude of troubles for which we are not responsible.

Now, two months after I returned from Iraq, a growing resistance and the persistence of widespread crime continue to bedevil American efforts to rebuild the country. This leaves our forces all the more vulnerable as they set out on to the sweltering streets and into the dusty alleyways on their daily patrols. We seem to be caught in a dynamic that threatens to spin beyond our control.