Rare Photos of Brazilian Tribe Spur Pleas to Protect It

November 22nd, 2016Spectacular new images of an uncontacted indigenous village in Brazil are stirring pleas from tribal leaders and rights advocates for government intervention to protect the settlement from illegal gold prospectors.

The aerial photographs show villagers gathered in the center of a traditional, circular structure inside the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, a sprawling reserve of rivers and upland forest situated astride the border with Venezuela.

The images were taken in mid-September by officials from Brazil’s indigenous affairs agency, Fundação Nacional do Índio—known by its acronym, FUNAI—on a surveillance flight over the reserve in the run-up to a joint operation with army troops and police agents to clear out thousands of wildcat gold miners. The same Yanomani Indians had been observed at a village in another location on a reconnaissance flight four years ago. But that communal dwelling was later abandoned, and officials feared for the fate of the group until the most recent sighting. Known as the Moxihatetema, the villagers have assiduously shunned contact with outsiders, even with other Yanomami communities.

Officials say they experienced both a sense of wonder and impending dread in their low-flying aircraft as they beheld the communal structure—built in an age-old style that has gone out of use among contacted Yanomami. “It’s incredible that they appear to be doing so well,” Guilherme Gnipper, the FUNAI agent who took the photographs, told National Geographic by phone from his home in Boa Vista, capital of the northern Amazonian state of Roraima. “Their gardens are huge, the people appeared to be healthy. But the gold strike is getting closer and closer.”

The natives showed little fear, making no effort to hide from the aircraft, Gnipper says. And unlike other communities of so-called “uncontacted tribes” that have been photographed in recent times, the Moxihatetema village appears to be completely devoid of industrial goods—such as aluminum pots, steel machetes, and cloth. “We saw no manufactured products whatsoever,” says Gnipper. “Nothing made of metal. They are living well—in complete isolation. It was like time travel.”

But that isolation could soon end, and officials as well as indigenous leaders fear it could end very badly.

“I am very concerned about my brothers, the Moxihatetema,” says Davi Kopenawa, a tribal shaman and president of the Hutukara Yanomami Association, which represents the estimated 22,000 Yanomami who live within the boundaries of the Brazilian reserve. (Another 16,000 natives live in an adjacent protected zone on the Venezuelan side of the border.)

Kopenawa says prospectors have been overheard on the streets Boa Vista discussing whether to launch a raid on the village. “I’m afraid the miners are going to seek out the village and kill everyone.”

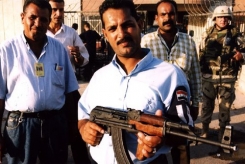

FUNAI officials and indigenous rights advocates say that concern is well-founded. Under the new conservative Brazilian government of President Michel Temer, FUNAI’s budget has been slashed by more than a third. The agents assigned to protect the Portugal-size Yanomami reserve are operating on a shoestring and find themselves overwhelmed by an estimated 5,000 prospectors illegally operating in Yanomami territory.

Mining operations have increased dramatically in recent months, and the miners are supplied not only via the vast territory’s network of rivers but by a series of clandestine airstrips as well. In an effort to curb the invasion, FUNAI has enlisted the support of a small contingent of Brazilian army troops and state military police. Government officials say that about a thousand prospectors have been expelled from the reserve since the operation began at the end of October.

An active gold strike is a mere 18 miles from the village, Kopenawa says. That encampment is supported by an airstrip, complicating efforts to dismantle it and expel the miners. Even peaceful contact with the village could spell disaster, he says, bringing death through diseases for which the isolated community has no immunity. “If the miners reach their village, they will contaminate them with white man’s disease.”

The Brazilian government established the Yanomami Indigenous Territory in the months preceding the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. At the time, the military launched a major effort, backed by aircraft and speed boats, to clear the region of illegal miners. But little by little, the prospectors have crept back in, often with the connivance of local political bosses and businessmen.

“When they expel the gold miners, they’re not tackling the root of the problem, which are the local politicians and some business leaders,” says Fiona Watson, a campaigner for the rights group Survival International. The organization has been spearheading an international effort to protect the Amazon’s last isolated tribes. “Uncontacted tribes like the one in the photograph are extremely vulnerable. The fact that they’re so near the gold mining operation puts them at enormous risk. It’s the constitutional duty of the Brazilian government to protect them.”

Besides the threats of violence and contagious disease, mining operations are also contaminating the waterways in the once pristine region with mercury. Widely used to separate gold from sediment, the toxic chemical accumulates in fish, posing a serious health hazard to indigenous riverbank dwellers who depend on aquatic life as a major source of protein.

The Yanomami gained international renown at the start of the new millennium, when Western scientists stood accused of perpetrating a host of misdeeds among the tribe in the course of their research. Widely known as the “Yanomami Controversy,” the imbroglio roiled the field of anthropology, with professional rivals trading accusations of using the tribe as an elaborate prop to further their own careers.

“The Brazilian government—FUNAI, the Federal Police, and the Brazilian army—should expel the miners from legally protected Yanomami land immediately,” Kopenawa implored. “The outside world should tell the Brazilian government to protect the Yanomami and expel the prospectors. It’s what we Yanomami want.”