Brazil Seeks to Save Isolated Tribe Threatened by Loggers

May 26th, 2016After years of delay, Brazil has approved the creation of a sprawling reserve that would protect a highly vulnerable tribe of isolated nomads along one of the most volatile frontier regions in the Amazon rain forest.

Tribal rights activists are hailing the decision, which will set in motion the labor-intensive process of physically marking the boundaries of the Kawahiva do Rio Pardo Indigenous Territory. The Kawahiva are a tribe of hunter-gatherers who for decades have been living on the run from logging crews and other intruders who covet the mineral and timber wealth in their species-rich forests.

The executive order came amid a flurry of decrees involving the recognition of land claims by indigenous groups. Facing a mounting economic crisis and corruption scandal that led to her recent ouster as president, Dilma Rousseff and her justice minister, Eugênio Aragãoa, hurriedly signed 11 executive orders aimed at establishing as many indigenous territories in her final days in office. Of those, only the Kawahiva reserve harbors an isolated tribe that maintains no contact with mainstream Brazilian society.

“This gives the Kawahiva a fighting chance,” says Fiona Watson, campaigns director for the tribal rights advocacy group Survival International, which has been leading a drive to pressure the Brazilian government to place the tribe’s land beyond the reach of loggers and other outside interests. “This is an important step. There’s no going back now.”

Brazil hosts the largest number of isolated indigenous groups of any country in the world. The Department of Isolated Indians, the agency charged with protecting such tribes, has confirmed the presence of 27 indigenous groups living in extreme isolation in Brazil’s vast Amazon region, and there may be several dozen more. Peru has the second largest number, with 14 or 15 isolated tribes.

The Kawahiva are estimated to have between 25 and 50 members. The tribe’s numbers are believed to have dwindled over years of enduring violent clashes with outsiders and harsh living conditions in a state of near-constant flight. Court-ordered anthropological studies used to determine the boundaries of the territory indicate that the nomads roam in small, family-sized groups over 1,590 square miles (4,120 square kilometers) of dense forest, an area the size of Rhode Island, in the northwestern corner of the central Amazonian state of Mato Grosso.

Granting such a large territory to just a few dozen people is not without controversy. Local business interests have vowed to fight the reserve or have its size reduced. But officials say that Brazil’s constitution clearly recognizes a tribe’s right to maintain its traditional way of life within boundaries that conform to their use of the land.

Despite signing the decrees in the waning days of her tenure, Rosseuff ordered recognition of less indigenous land than any other president since Brazil emerged from military dictatorship in 1985. Rights groups are concerned about a growing movement in Brazil’s Congress, fomented by the powerful agribusiness lobby, to reverse protections for indigenous lands and cultures.

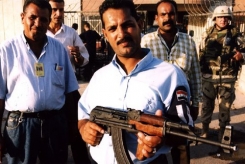

The region is one of the most violent and lawless in all of Brazil, characterized by rampant illegal logging, theft of public land, and widespread resentment toward federal officials responsible for safeguarding the rain forest and its indigenous inhabitants. Precious hardwoods have been logged out of most of the surrounding forests, Indian protection agents say, putting the timber-rich Kawahiva lands in the crosshairs.

“Invasions of the territory have been very intense,” says Elias Bigio, technical advisor to the government’s Fundação Nacional do Índio, or the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI). “The perpetrators are very aggressive. They have no fear. They respect nothing.”

Bigio, former director of FUNAI’s Department of Isolated Indians, says agents assigned to monitor and protect Kawahiva land are bracing for intensified incursions—and possible revenge attacks—in the wake of the Justice Ministry’s announcement.

“We know that invasions could increase, along with retaliations against the isolated Kawahiva and FUNAI,” he says. “The loggers are bound to view the demarcation of the Indigenous Territory as a huge loss for their profits.”

In response to stepped-up government vigilance, logging gangs are deploying new tactics to evade detection as they trespass into Kawahiva land to steal valuable timber. Lumberjacks enter the forest by foot or motorbike along narrow trails, then set about toppling precious hardwoods, including mahogany, cedar, ipê, and Brazil-nut trees. Only at the last minute do they bring in heavy machinery to cut roads to haul out the logs.

“They create small clearings to gather timber under the forest canopy to avoid attracting attention,” says Evandro Selva, who heads field operations in northwestern Mato Grosso for Brazil’s environmental protection agency, Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis (IBAMA). “When it comes time to take out the logs, they bring in a tractor and cut a track for the trucks to come in. It’s very quick.” By the time IBAMA agents arrive on the scene, Selva says, the loggers have made off with their ill-gotten gains

The rough-and-tumble municipality of Colniza, which overlaps Kawhiva land, is the focal point of some of the most intense rain forest destruction in the state. Mato Grosso Governor Pedro Taques told delegates gathered last year at the United Nations climate change conference in Paris that 92 percent of all logging and land clearing in his state is conducted illegally. While deforestation rates have plummeted nationally in recent years, Mato Grosso has bucked the trend, with illegal logging and clear-cutting continuing unabated through 2015. Taques has pledged to end illegal deforestation in Mato Grosso by 2020.

The region is also rife with grilheiros—land speculators—who clear forest on public land, then draw up phony titles to sell off the lots. Bigio said his team recently came across a path hacked nine miles (15 kilometers) into Kawahiva territory that led to lots marked by surveyor flags for clearing.

A small cadre of wilderness scouts assigned to FUNAI’s Madirinha-Juruena Ethno-Environmental Protection Front have been patrolling Kawahiva territory for years. Constantly on the lookout for intruders, the agents also check on the well-being of the tribal nomads, documenting their presence while seeking to avoid direct contact. Last June, the team came upon a temporary lean-to erected by Kawahiva hunters.

Reached by internet phone at the FUNAI post inside the reserve, the protection front’s chief, Jair Candor, said the Indians fled just moments before he and his colleagues arrived. They left behind their scant belongings and a smoldering campfire. Candor estimated that a dozen people were sheltering in the lean-to. “It was clean, everything neatly arranged,” he says. “They must have been nearby. They must have been watching us.”

Such discoveries are usually a welcome sign that the Indians are doing well. But his team later detected a large area of deforested land, where loggers and land speculators were setting up operations. It was a mere six miles from the Kawahiva encampment. With the help of agents from IBAMA, the operation was shut down, the culprits expelled. “We managed to get them out of there,” Candor says of the intruders. But without permanent reinforcement from IBAMA or the police, he says, “there’s always the risk they will come back.”

Five years ago, Candor filmed dramatic, up-close footage of a band of Kawahiva hunters making their way through the forest as he hid behind a tree. After the Department of Isolated Indians released the video in 2013, local politicians accused FUNAI of “planting Indians” and staging the scene to bolster the case to place the territory off-limits to development.

Officials caution that it could take many months before the task gets under way to delimit the 200-mile (329-kilometer) perimeter of the Kawahiva do Rio Pardo Indigenous Territory. The process could also become mired by bureaucratic inertia and political infighting, leaving the land and the tribe it harbors vulnerable to potentially fatal incursions.