A Death Foretold

June 8th, 2011

In Brazil’s violent backwoods, environmental destruction and murder go hand in hand

by Scott Wallace

posted on NationalGeographic.com

Late last month the Brazilian Congress passed a bill that if it becomes law would ease restrictions on rain-forest clearing and make it easier than ever to mow down the Amazon. That same day, 800 miles north of the parliamentary chamber in Brasilia, assailants ambushed and killed a married couple whose opposition to environmental crimes had placed them in the crosshairs of those who most stand to gain from the new legislation.

It’s a nauseatingly familiar story. Over the past 20 years, there have been more than 1,200 murders related to land conflict in Brazil’s Amazon region. Most of the victims, like the married activists Zé Claudio Ribeiro and Maria do Espírito Santo, were defenders of the rain forest—people seeking sustainable alternatives to the plunder-for-profit schemes that characterize much of what passes for “development” in the Amazon.

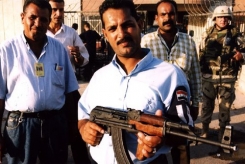

Photo by Felipe Milanez. Zé Claudio Ribeiro poses last year with one of the ancient Brazil nut trees he defended with his life.

The state of Pará—where Zé Claudio and Maria were ambushed on their motorbike as they crossed a rickety bridge—holds an especially notorious reputation for environmental destruction and organized violence. Pará is the bloodiest state in Brazil, accounting for nearly half of all land-related deaths in recent decades. It sprawls across an area larger than the states of Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico combined. Picture a tropical version of the Wild West, stripped of the romance, where loggers and ranchers muscle their way onto public land as though they own the place and impose a law of the jungle with their hired thugs. Those who have the nerve to protest soon find themselves the targets of escalating threats. If they persist, they find themselves staring down the gun barrels of those come to make good on the threats.

The couple had riled many interests in southeastern Pará. They were expelled from the board of directors of their cooperative after they accused board members of conspiring with loggers and charcoal producers to sell off majestic, centuries-old Brazil nut trees within the reserve. (The cutting of castanha trees is expressly prohibited by Brazilian law.) They filed grievances on behalf of neighbors whose land had been invaded, and they exposed the machinations of land grabbers who used phony identities to conceal their criminal dealings. Yet their denunciations led nowhere. No investigations. No indictments. No police protection. As journalist Felipe Milanez, a former staff writer for the Brazilian edition of National Geographic, puts it: “Those who filed the complaints were left exposed.”

Four days after the double murder, another small cultivator, Herivelto Pereira dos Santos, was shot dead near the same extractive reserve where Zé Claudio and Maria lived and worked. After surviving the initial shooting, dos Santos staggered down the road to find help, when the assassins returned to finish the job.

The government of the new president Dilma Roussef has promised to beef up security for those living under threat of death. The Pastoral Land Commission (CPT), a Catholic rights agency, says the lives of at least 125 activist forest defenders are in danger. But President Roussef must also decide what to do with the new bill when it lands on her desk. Will she sign it into law? Whether she does or not, some believe Brazil’s Congress has already cast a decisive vote that points toward dark times to come.

“The murder of the married couple could have made them into martyrs for their defense of the forest,” Milanez reported from Pará. “But on that same day, the representatives of the nation signaled a different course for the future, one in which the forest—if it continues to exist—will have no importance for Brazilians, where the biodiversity that so delighted Zé Claudio Ribeiro da Silva and Dona Maria do Espírito Santo runs the risk of being reduced to a patch of pastureland. In a field drenched in blood.”